Last week’s EPA decision adds insult to injury for our already vulnerable communities.

Perhaps you missed it. There’s a lot going on right now. But amidst all the COVID-19 headlines last week, the EPA decided that it is not “appropriate and necessary” for the government to limit emissions of mercury and other hazardous air pollutants from power plants.

This is not a roll-back of a regulation. It’s more nuanced than that. It’s a high-stakes procedural move with two important implications:

First, it scraps the legal basis for the Mercury and Air Toxics Standards (MATS) which limit hazardous air pollution from coal and oil-fired power plants. Having knocked the legal foundations out from under this important regulation, I think there’s a real risk that power plants will find ways to dial back on compliance in the future.

Second, it sets a dangerous precedent for how the benefits and costs of federal environmental regulations are assessed. The ruling removes significant health benefits from cost-benefit consideration on the grounds that they are not directly targeted by MATS.

This announcement comes at a time when the country is reeling from the global coronavirus pandemic. Protecting public health is top of mind. We’ve all become keenly aware of how actions we take can indirectly protect the health of the most vulnerable among us. With these benefits in mind, we are taking action.

Meanwhile, the EPA has decided that the indirect health benefits of pollution reductions should not be considered in regulatory cost-benefit analysis. This decision departs recklessly from standard practices for responsible public decision-making.

Some colleagues and I recently published this paper (based on our longer report) which points out deep flaws in this EPA decision. The agency’s own Science Advisory Board released a report calling for a “do-over”. Hundreds of thousands of public comments raise concerns. Even the electricity sector stands in opposition. The Trump EPA response: To hell with it. We are pushing ahead.

To understand what this means, we need to remember how we got here.

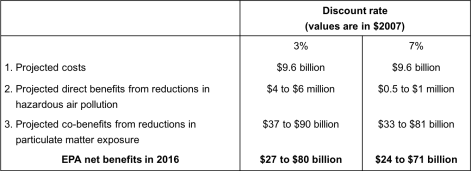

The Mercury and Air Toxics Standards limits the emissions of mercury and other hazardous air pollutants (HAPs) from power plants. To justify the rule, the EPA must demonstrate that it is appropriate and necessary. Back in 2011, the EPA supported this argument with a detailed analysis that projected big public health benefits from the power plant emissions reductions expected under the regulation. The table below, taken from the 2011 analysis, shows monetized benefits far exceeding the costs.

There were some serious bumps on the road to implementation. But power plants began complying in 2016. The industry has since invested billions to install pollution abatement equipment in order to meet MATS requirements.

Last year, the Trump EPA started working to reverse the appropriate and necessary finding. The agency issued this six-page memo that re-interprets the 2011 cost-benefit analysis. There’s no new information here. The big change is that the “co-benefits” – health benefits that result indirectly from MATS compliance—have been wiped off the cost-benefit board. If we ignore these benefits (row 3 in the table above), MATS appears to fail the cost-benefit test.

There are many reasons to be concerned about this maneuver. Let me unpack three:

- Co-benefits are real benefits

When power plants reduce mercury emissions, they also reduce emissions of precursors to harmful particulate matter (PM). Reducing exposure to small particulates saves lives. These benefits are referred to as “co-benefits” because they are caused by – but not directly targeted by – the regulation.

If a policy will generate big health benefits, directly or indirectly, these should be counted. Federal agencies are under Executive Order to weigh the available evidence on all significant costs and benefits in their regulatory assessments. This is also required under the EPA’s own guidelines for economic analysis.

An official decision that eliminates or reduces consideration of co-benefits sets a troubling precedent for future regulatory decisions. If this approach becomes standard, it becomes much more difficult for the EPA to justify socially beneficial regulations. Greenhouse gas emissions regulations- which can deliver significant reductions in local air pollution- are one important example.

- Direct benefits estimates are outdated and incomplete

The 2011 direct benefit projections that serve as a basis for last week’s decision reflect only one health benefit from reducing mercury emissions: improvements in the IQs of children whose families catch and eat freshwater fish. This narrow focus explains why those 2011 direct benefits estimates are so small.

A decade later, we know a lot more about how power-plant mercury accumulates in commercial seafood consumed by many Americans. In addition, recent research suggests that mercury exposure could cause cardiovascular problems. If these additional health impacts were accounted for, the direct benefits of HAP reductions would look quite different. But the 2020 EPA decision is still referencing outdated and incomplete 2011 benefits numbers.

- Costs are largely in the past

To comply with MATS, billions have been invested in equipment that scrubs harmful pollution out of power plant emissions. In other words, the investment costs that comprise the majority of the 2011 cost projections have already been incurred. Going forward, the costs we need to consider are the costs of operating this pollution abatement equipment. Estimates I’ve seen range from $1.80/MWh to as high as $7.92/MWh (a non-trivial increase in coal-fired electricity generation costs).

By dismissing the legal basis for the rule, MATS is left wide open to the challenge that the pollution controls are no longer legally required. If I were a coal plant operator, I might read between the lines of this decision and conclude that the EPA is not so concerned about enforcing MATS going forward.

Coal plants across the U.S. are struggling to compete with natural gas and renewables. If MATS requirements are not there to keep pollution controls switched on, plants in competitive electricity markets will have an incentive to turn this equipment off to save a few dollars/MWh. If this happens, downwind communities will pay a hefty health price.

Adding insult to injury

You would think that a high-stakes regulatory decision like this would merit an analysis update given that almost a decade has passed since the original assessment was done. The reams of data and scientific evidence that have accumulated since 2011 could provide a much more accurate evaluation of the rule’s benefits and costs, in addition to a more informed basis for re-evaluating the appropriate and necessary finding. Instead, this EPA has dusted off a stale 2011 analysis, deleted the co-benefits, and declared the rule unnecessary and/or inappropriate.

The timing of this decision feels particularly callous because the communities that have historically been most exposed to high levels of air pollution are the ones being hit hardest by the COVID-19 crisis. This recent study suggests that even small increases in long-term exposure to particulate matter significantly increase COVID-19 fatality risk.

The Trump administration assures us it is putting “safety first” during this COVID-19 epidemic. But in the background, Trump appointees have been doing quite the opposite with decision after decision after decision. This MATS reversal has the potential to do real damage. But if there is good news to be found in this story, it’s that it will take time to play out. One more reason to work hard to course correct in November.

Keep up with Energy Institute blogs, research, and events on Twitter @energyathaas

Suggested citation: Fowlie, Meredith. “What Just Happened to the Mercury Rule?” Energy Institute Blog, UC Berkeley, April 20, 2020, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2020/04/20/what-just-happened-to-the-mercury-rule/

You must be logged in to post a comment.